7 Hybrid Assessments

Combining qualitative and quantitative data is essential to understand issues as complex as mobility fully. However, analyzing both data types can be challenging, and integrating them into a cohesive analysis is often tricky. Here, hybrid assessments can help bridge the gap between qualitative and quantitative studies.

7.1 Why do we need them?

In the next few sections, we will explore various walkability measures, including an area’s built and natural environment and other essential aspects. While GIS techniques and macro data sources can provide a baseline understanding of the walkability of a site, they often miss out on the unique issues and experiences that residents face on a day-to-day basis.

In early 2023, Sensing Local, an organization that works on urban and environmental issues in Indian cities, commenced a series of walkability for 24 wards in Bangalore (ByIffath 2022). As of writing this, more than 139 km of footpaths have been audited in 10 wards has been completed. These audits, using collaborative tools and with the help of community volunteers, mapped various street features, such as footpath conditions, street litter, encroachment, and streetlight presence. Although these are important indicators of the neighbourhoods they visited, there may be other problems that these criteria missed.

To better understand the region, another audit of Bangalore’s wards was conducted by ichangemycity in 2016 and produced data for all wards, including Ejipura (ichangemycity 2016). This audit included a broader set of criteria, such as:

- Civic Facilities: Presence of parks, public toilets, bus stops, and waste collection centres.

- Quality of life: Walkability of footpaths and conditions of significant crossings, streetlight presence, and other citizen grievances.

- Budget allocation: Areas of budget allocations and overview of budgeted works.

This more comprehensive approach not only provides an understanding of the accessibility of various amenities but also includes qualitative data on what the residents feel is an issue.

As researchers, we often study areas that we aren’t familiar with. Therefore, standardized metrics, such as sidewalk measurements, street lighting, and footpath conditions, are crucial for providing a foundational understanding of the walkability of an area. However, relying solely on these metrics can limit our understanding of residents’ unique issues and experiences. Qualitative research can provide valuable insights into the lived experiences of individuals in the community. For example, an on-ground study conducted by community volunteers can reveal micro-scale insights that data analysis using GIS techniques and macro data sources may miss. Section 14.3 shows some unique insights that can be gathered from interviews.

7.2 Grassroots approach

We can use a grassroots approach to designing audits to help fill these quantitative research gaps, often created based on standardized metrics.

Grassroots, also known as bottom-top approaches, focus on collecting data from participants locally instead of entirely relying on higher-level data sources. The grassroots process is particularly relevant in fields such as community development, social justice, and public health, where understanding the experiences and needs of the local community is critical to developing effective interventions or policies and can similarly be applied to inform the assessment process, which can ultimately lead to more effective and inclusive solutions (Knapskog et al. 2019).

7.3 Differences in methods

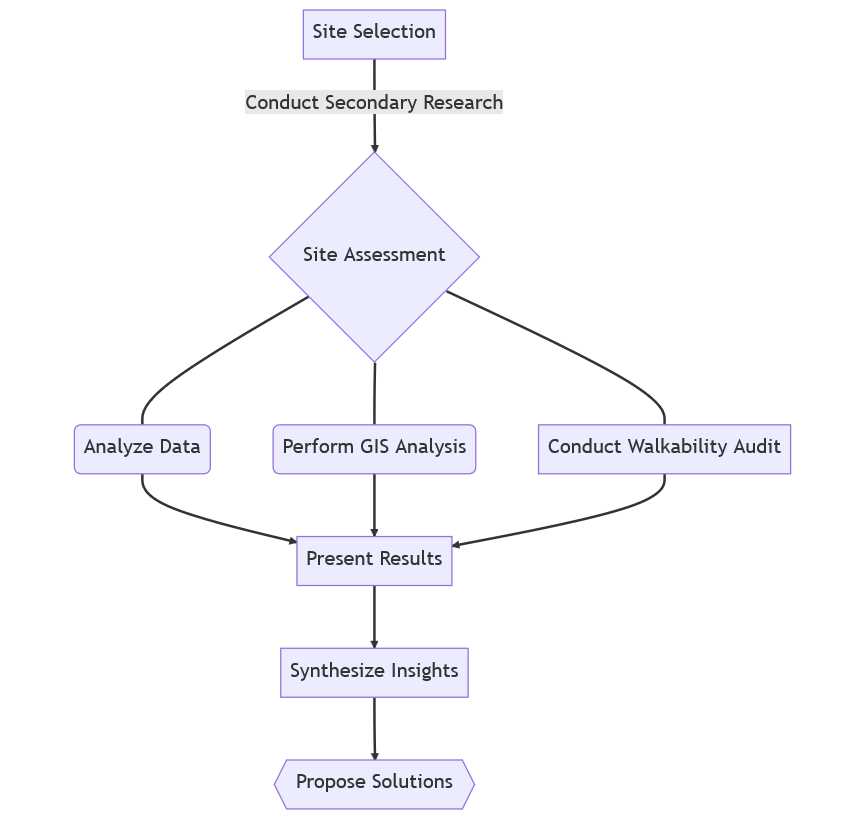

In most of the walkability audits I have encountered, and others have studied, the qualitative features of streets fail to attract the necessary attention and aren’t investigated. (Aghaabbasi et al. 2018). Most studies follow the framework shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: A typical walkability assessment

This isn’t bad in itself, and if the study aims to audit an environment with the specific intention of only assessing things like sidewalks and streets, that is okay. However, it may not capture the lived experiences of the people who use the space daily. Engaging with local residents and considering their perspectives is essential to gain a more holistic understanding of walkability.

Based on my experience in Ejipura, taking a different approach helped. Instead of assessing standard walkability measures, I went to the site on multiple visits to see what I needed improvement. Since these observations are still detached from what the residents experienced daily, I conducted interviews and other participatory activities to try to answer the fundamental question I outlined above:

What does walkability mean to the people who live there?

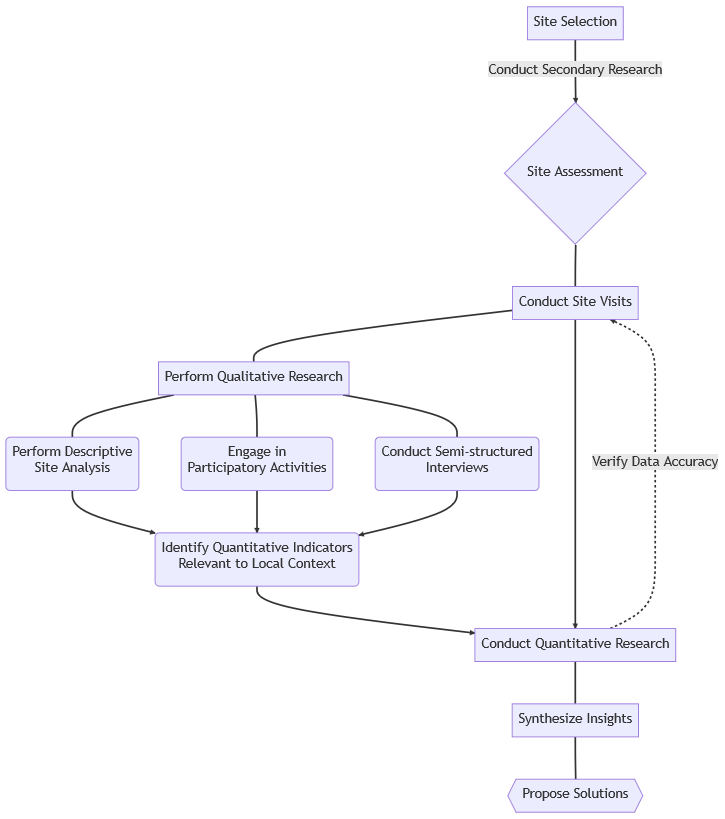

This process differs from the flow I illustrated above and uses qualitative research to develop the indicators I must assess. Figure 7.2 outlines my process while studying Ejipura.

Figure 7.2: Allowing qualitative research to surface quantitative measures

This process involved qualitative research to develop indicators that emerged from local knowledge. Using site visits as an essential part of verifying results, I ensured that my insights were grounded in the community context. This approach allowed me to tailor my findings to the specific needs of Ejipura rather than attempting to impose Western models of development that may not be appropriate for Indian cities.

One challenge of using qualitative research is that it can be perceived as unscalable. However, in the following sections, I will demonstrate how I used qualitative data to analyze the environment quantitatively based on the insights gained from interviews and observations. This method can help to bridge the gap between qualitative and quantitative approaches, providing a more comprehensive understanding of walkability in Indian cities. These methods will be demonstrated using Ejipura as the context but can be replicated easily for any other region. Let’s get into it!